“These are the boys of Pointe du Hoc.

These are the men who took the cliffs.

These are the champions who helped free a continent.

These are the heroes who helped end a war.”

-President Reagan, address at Pointe du Hoc, 40th anniversary of D-Day, 1984

While Rangers of the 75th Ranger Regiment in the Global War on Terror have become the Army’s premier special operations raid force, their modern legacy was birthed storming the beaches of Normandy and climbing a nine-story cliff. The mission at Pointe du Hoc included destroying six 155 mm howitzers, preventing Germans from firing artillery onto the allies wading onto Omaha and Utah beaches, both within range of the guns. In a matter of hours, the 2nd Ranger Battalion, led by Lieutenant Colonel James Earl Rudder, accomplished their primary objective with speed, violence of action, audacious leaders, and grit. For the Americans, the invasion began with Rangers leading the way.

PROBLEMS ON APPROACH

The Rangers planned to arrive at 0630 on the slim coastline below the cliffs. Their first wave consisted of nine British landing craft assaults (LCA’s), a supply LCA, and four amphibious trucks called DUKW’s specially equipped for the Ranger mission. After a five-day weather hold aboard British ships, the call came over the loudspeaker for the Rangers to man their landing craft. The time was a little after 4 am on June 6th. Although their scheduled landing time was 0630, they ran into delays along the way.

Upon their approach, “Colonel Rudder and many of us had noticed that the point we were going to did not look like the point we studied,” recalled First Sergeant Lomell. Instead of heading towards Pointe du Hoc, the British coxswain improperly steered the craft towards Pointe de la Percée, halfway between Dog Sector of Omaha Beach near the Vierville Draw and their objective at the Pointe.

As a result, the flotilla had to run a three-mile gauntlet of coastline under heavy enemy fire. The error cost them about forty minutes and a DUKW sunk by a 20 mm shell. This extra time allowed the Germans to react and refortify their positions after the air and naval bombardment, which ceased at 0630, the expected time the Rangers were to hit the ground. Lieutenant Jim Eikner, a Ranger officer on one of the LCAs, remembered: “ . . . bailing water with our helmets, dodging bullets, and vomiting all at the same time.” The assault element finally reached the shore at approximately 0710.

CLIMBING THE CLIFFS

Looking up at the cliff of Pointe du Hoc ten years later, LTC Rudder said to his son and a reporter, “Will you tell me how we did this? Anybody would be a fool to try this. It was crazy then, and it’s crazy now.” The cliffs the Rangers scaled under enemy fire stood almost one hundred feet tall. When they landed, the beach was only ten meters wide and shrinking due to the rising tide. The aerial and naval bombardments caused clay from the cliffs to fall on the beach, making the surface slippery. The Rangers now had to conquer the cliffs or be stranded on the dwindling foothold.

The Rangers utilized some creative methods for scaling the almost ten-story cliffs. The Rangers leaned against the cliffs using twenty-five-meter extension ladders carried by the DUKWs and donated by the London Fire Department. Unfortunately, only three made it to shore. The Rangers ran into a few problems with the ladders. There were craters everywhere from the bombardment, the beach was slippery from the clay, and they received enfilading fire from their left flank.

Sergeant Stivinson, one of the Rangers who managed to climb up to the top of a ladder started firing his machine gun and swayed back and forth like a metronome. Lieutenant Elmer Vermeer remembered “[t]he ladder was swaying at about a forty-five-degree angle—both ways. Stivinson would fire short bursts as he passed over the cliff at the top of the arch, but the DUKW floundered so badly that they had to bring the fire ladder back down.” While an innovative mode to scale the cliff, the most effective method was by rope.

As the landing crafts approached the shore, they launched ropes as they hit the beach. First Sergeant Lomell remembered, “we pressed the buttons [on the landing craft] as the ramp [dropped] down and those six ropes and grappling hooks [went] over the tops of the cliffs to dig in to support their weight.” They also had hand rockets they launched over the top of the cliff when they landed. As soon as they disembarked the landing craft, the men started climbing. Using the fallen clay, the ropes, ladders and their bayonets, the Rangers ascended amidst German machine gun fire and “potato masher” grenades the enemy rolled off the side of the cliff. Despite the resistance, some of the men reached the top within the first fifteen minutes.

FIRE SUPPORT FROM SEA AND AIR

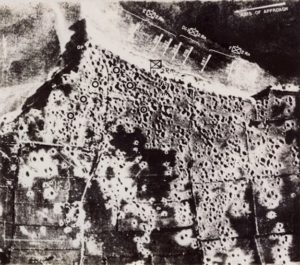

One of the most important elements of the Rangers’ landing was their support from the air and sea. They received weeks of prior preparation by heavy bombers from the 8th Air Force. Altogether, the aircraft hit the area around Pointe du Hoc with ten kilotons of high explosives, the equivalent of the explosive power of the atomic bomb used at Hiroshima. The Battleship Texas prepped the area for twenty minutes with fourteen inch shells, but lifted its fire at 0630 when they expected the Rangers to arrive. It later resumed its support as the Rangers pushed inland.

By 1730, two other ships relieved the Battleship Texas after it expended about seventy percent of its ammunition in its support for the Rangers. As the Rangers continued their assault, the HMS Tallybont and USS Satterlee provided additional fire support, driving the Germans away from the coastline. Lieutenant Vermeer remembered when they climbed up the cliff, “ . . . not one of the radios which they had brought in to direct fire from the Navy ships was working. They had all become water soaked in the trip across the channel.” Lieutenant Eikner resorted to quick thinking and used an old World War I signal lamp to eliminate the enfilading fire from their left flank. By manipulating the shutters on the lamp, he communicated with the USS Satterlee and adjusted naval gunfire to destroy the machine gun nest causing the most disruption. The Rangers’ use of combined arms, innovation, and alternate means of communication saved many lives that day.

MISSION ACCOMPLISHMENT

Probably the most amazing feat the Rangers accomplished on D-Day was not the actual scaling of the cliffs, but rather the actions they performed after they reached the top. Each platoon had an assigned objective beyond their infiltration method of climbing Pointe du Hoc. To add to the confusion of the morning, the Rangers atop the Pointe found terrain which they thought looked like the surface of the moon due to the prior shelling and ordinance dropped on the piece of key terrain. After using the first few craters to reorganize, the Rangers immediately pushed on to their objectives. When they seized the location where they expected the 155 mm guns, they found only telephone poles and abandoned casemates, a German ruse.

The Rangers continued to push their small patrols inland and later found the guns 1,200 yards from the cliffs. First Sergeant Len Lomell was one of the two men who found the six 155 mm guns. They found them in an apple orchard under trees and camouflage netting. Staff Sergeant Jack Kuhn, First Sergeant Lomell’s companion, recalled “the guns were in a line, all of them in a firing position, their barrels raised 30 or 40 degrees and aimed toward Utah Beach.” Nearby, with about 100 Germans across the orchard, SSG Kuhn pulled overwatch for his buddy, First Sergeant Lomell.

Already wounded from a gunshot he received in his side during the initial climb to the top of the bluff, Lomell decided to maneuver to the guns alone. Despite his wounds, he dashed to the guns, disabled two of them by melting the traversing mechanisms with thermite grenades, and hastily smashed another of the guns’ sights with the butt of his Thompson submachine gun. Lomell and Kuhn returned to their comrades to obtain more incendiary grenades and shuttled back to the guns. Placing thermite grenades on the remaining guns, Lomell melted the traversing mechanisms and breech blocks, putting all six of the guns out of service.

The success at Pointe du Hoc can be accredited to a number of factors including achieving surprise, fire support, the Rangers’ training and initiative, and the courage of the small unit leaders and Rangers who fought there. In addition, their assault across the cratered terrain at the top of the cliffs succeeded because the German observation post and the guns were primarily protected from the land, not the sea. The Germans did not believe an assault on Pointe du Hoc would come from the ocean. Even some of the American officers doubted this plan. Admiral Hall, an intelligence officer, commented, “It can’t be done. Three old women with brooms could keep the Rangers from climbing that cliff.” But Lieutenant Colonel Rudder had faith in his men and their abilities. They trained hard and prepared for the task, physically and mentally.

Had the six guns been in operation at the time of the invasion, it is tough to determine what effect they would have had on the American beaches. What remains important is the intelligence reported six guns ready to inflict massive casualties on American soldiers when the invasion began. The brave men of the 2nd Ranger Battalion eliminated their mission to destroy the guns and protect the allies storming the beaches. According to First Sergeant Len Lomell, the Rangers “knew it was the most dangerous mission on D-Day. Ten thousand lives depended on us and thousands of ships.” Lieutenant Eikner supported Lomell’s statement when he pointed out, “ . . . had we not been there we felt quite sure that those guns would have been put into operation and they would have brought much death and destruction down on our men on the beaches and our ships at sea.”

The Rangers received a mission they knew to be critical to the entire invasion. When these courageous men found the guns, they were functional, ready to fire, and trained on Utah Beach. The Rangers carried out their mission in a heroic and innovative manner and led the way across Europe, from Normandy on D-Day to the Hurtgen Forest. These 225 brave men were some of the first Americans to accomplish their D-Day objectives. Their valiant efforts marked the beginning of the “Great Crusade,” and the beginning of the end for Hitler and his domination of the European continent.

_______________

This first appeared in The Havok Journal on May 31, 2019.

Mike grew up in Akron, Ohio. He is an Infantry Officer in the U.S. Army with experience in special operations, counterterrorism, and counterinsurgency operations over twelve deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan, including with the 75th Ranger Regiment. He’s been awarded the Bronze Star Medal with Valor and two Purple Hearts for wounds sustained in combat. He is a graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point, a Downing Scholar, and holds masters degrees from both Princeton and Liberty Universities. The views expressed on this website are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army or DoD.

_______________

WORKS CITED

Ambrose, Stephen E. D-Day, June 6, 1944: The Climactic Battle of World War II. New York: Touchstone, 1995.

Ambrose, Stephen E. The Victors, Eisenhower and His Boys: The Men of World War II. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1998.

Brinkley, Douglas. The Boys of Pointe du Hoc: Ronald Reagan, D-Day, and the U.S. Army 2nd Ranger Battalion. New York: HarperCollins, 2005.

Harrison, Gordon A. Cross-Channel Attack. Washington: Center of Military History, 1993.

Lane, Ronald L. Rudder’s Rangers. Manassas: Ranger Associates, 1979.

Lomell, Len. Interview by West Point History Department. Accessed 11 April 2004. Available from http://www.dean.usma.edu/history/web03/staff%20rides%20site/, Internet.

Ryan, Cornelius. The Longest Day: June 6, 1944. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1959.

Shine, Alexander P. Stepchildren: The Rangers of World War II. Boston: Harvard University, 1970.

Simpson, Kevin. “Ex-Ranger, 74, tells hero’s tale.” Denver Post, 4 June, 1994.

Tutt, Bob. “D-Day, 50 Years Later, The beginning of the end, Ranger unit scaled cliffs while under enemy fire.” Houston Chronicle, 31 May 1994.

Vermeer, Elmer. “Pointe du hoc.” Voices of D-Day: The Story of the Allied Invasion Told by Those Who Were There. Edited by Ronald J. Drez. Louisiana State University Press, 1994.

As the Voice of the Veteran Community, The Havok Journal seeks to publish a variety of perspectives on a number of sensitive subjects. Unless specifically noted otherwise, nothing we publish is an official point of view of The Havok Journal or any part of the U.S. government.

© 2023 The Havok Journal

The Havok Journal welcomes re-posting of our original content as long as it is done in compliance with our Terms of Use.

Leave a Reply